More and more people around you are being diagnosed with depression or ADHD, but is that an illusion? There is an epidemic in America, but it’s not an epidemic of psychiatric disorders—it’s an epidemic of over-diagnosis that’s making billions for pharmaceutical companies and the doctors prescribing these drugs.

The Daily Beast, By Jesse Singal

June 21, 2013

The next time you’re in a crowded room, look around. A scary percentage of the people in the room with you are suffering from a mental disorder.

Or at least that’s what we’ve been led to believe, that the United States has a crisis on its hands when it comes to mental illness. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), the most recent edition of the bible for psychiatric diagnosis, offers up the current “official” view on what the establishment believes separates the normal from the disordered. Both it and its predecessors have received heaps of criticism for turning the everyday highs and lows of human experience into diseases.

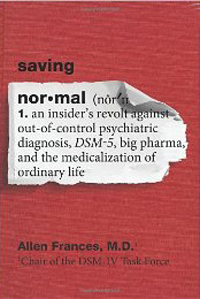

In Saving Normal: An Insider’s Revolt Against Out-of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life, Allen Frances, a semi-retired psychiatrist who served as the chair of the task force behind the DSM-IV, uses the release of the DSM-5, the methodology behind which he calls “egregiously reckless,” as a springboard to offer up a stinging rebuke of the explosive rate of psychiatric diagnosis in the U.S.

According to Frances, the U.S. is experiencing a dangerous moment in which political and financial forces are pushing people to think of themselves as abnormal, and “the counterbalancing forces pushing normal don’t remotely counterbalance and aren’t nearly forceful enough.” In other words, there are many people who profit from the idea that a staggering proportion of Americans are mentally ill, and these groups are powerful, well organized, and politically effective. The argument that things aren’t that bad—that the hysteria over attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder or autism is a bit overblown and not backed up by empirical literature—is much harder to make. Given a screeching demagogue and an evenhanded, mild-mannered technocrat, people will always be more drawn to the former.

Frances, like psychiatrist Edward Shorter, the author of How Everyone Became Depressed: The Rise and Fall of the Nervous Breakdown, believes in psychiatry when it is done correctly. The right medication prescribed in the right dosage at the right time can save a life. But we’ve convinced ourselves that a variety of merely human experience—temporary bouts of sadness or excitement or distraction—are in fact pathologies that need to be blasted at with drugs. The companies that make these drugs are all too happy to help agitate us into a state of hypochondria, and more or less make up certain “diseases” by dint of their influence within the medical establishment. The media, meanwhile, eagerly laps up new and exciting mental afflictions, reporting on them credulously.

Two quirks often convince people that drugs work when they do not. The first is that most people naturally return to their baseline state after experiencing a short period of, say, depression or mania. The second is the placebo effect, which will often cause anything presented as medication to “work.” If I visit a psychiatrist because I’ve been feeling pretty sad for a week, and I’m prescribed an antidepressant, I may decide that the medication “works” because I soon return to my standard level of happiness. In this case psychiatry has taken a normal part of the human experience—feeling crappy for a little while—and pathologized it, potentially leading me to become dependent on a drug that may have dangerous side effects.

Frances’s book is full of examples like this—of powerful antipsychotics given to 3-year-olds, of doctors prescribing dangerous combinations of drugs at the hint of a disorder. His preferred approach upon encountering someone who might have a problem—“watchful waiting”—is antithetical to the current trend in psychiatry, where the automatic response to any perceived problem is to prescribe, prescribe, and prescribe some more.

But Saving Normal is about a bigger, broader story than simply blaming the drug companies and the media. Rather, the culprit here is a variety of interlocking factors. Complex systems lead to massive over-diagnosis. Take, for example, the sudden and recent “explosion” of ADHD among the nation’s youths. Frances lists six factors that contribute to the “epidemic”:

Working changes in DSM-IV; heavy drug-company marketing to doctors and advertising to the general public; extensive media coverage; pressure from harried parents and teachers to control unruly children; extra time given on tests and extra school services for those with an ADHD diagnosis; and finally, the widespread misuse of prescription stimulants for general performance enhancement and recreation.

So while Frances does direct a fair amount of his ire at the drug companies, it’s not just about Big Pharma steamrolling everyone, effectively forcing drugs down their throat. Your kid is falling behind in school, so don’t you want to do anything you can to help? All your colleagues are prescribing their patients a drug that works wonders to promote concentration, so do you really want to be the only doctor in the building who isn’t a part of this exciting new pharmacological breakthrough? The current state of affairs rose up organically out of many individual decisions influenced by inadequate regulation and skewed incentives for the people who manufacture, advertise, and prescribe these drugs.

Frances, having been immersed in various psychiatric bureaucracies, has the eye for how multifaceted, interdependent systems function. But he is a better commentator than a reporter, and the reader gets the sense that he or she is in an airplane, and the captain keeps pointing out landmarks 40,000 feet down, only the most prominent features of which are visible. Frances rarely gets into specifics, but he does give some, well, prescriptions. He argues that it is a mistake to allow drug companies to advertise directly to consumers, which is not the norm in the developed world outside the U.S. But Congress and federal regulators aren’t ever likely to take up the issue, which would open up all sorts of constitutional issues. He also argues that the practice of diagnosing criminal suspects claiming to be mentally ill should be curbed except in the clearest cases. “Bad should usually trump mad,” he writes. But there’s a consensus among reform-minded observers of the criminal-justice system that offenders are dangerously under-treated for mental disorders.

America’s diagnosis is clear. We have convinced ourselves that we are a sick, troubled people, and the result has been endless, largely harmful prescription—and endless profits for the drug companies. The first step toward getting out of this mess is to understand just how many of our psychiatric maladies are pure fictions.

SHARE YOUR STORY/COMMENT