Esquire Magazine – March 27, 2014

By Ryan D’Agostino

By the time they reach high school, nearly 20 percent of all American boys will be diagnosed with ADHD. Millions of those boys will be prescribed a powerful stimulant to “normalize” them. A great many of those boys will suffer serious side effects from those drugs. The shocking truth is that many of those diagnoses are wrong, and that most of those boys are being drugged for no good reason—simply for being boys. It’s time we recognize this as a crisis.

If you have a son, you have a one-in-seven chance that he has been diagnosed with ADHD. If you have a son who has been diagnosed, it’s more than likely that he has been prescribed a stimulant—the most famous brand names are Ritalin and Adderall; newer ones include Vyvanse and Concerta—to deal with the symptoms of that psychiatric condition.

The Drug Enforcement Administration classifies stimulants as Schedule II drugs, defined as having a “high potential for abuse” and “with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence.” (According to a University of Michigan study, Adderall is the most abused brand-name drug among high school seniors.) In addition to stimulants like Ritalin, Adderall, Vyvanse, and Concerta, Schedule II drugs include cocaine, methamphetamine, Demerol, and OxyContin.

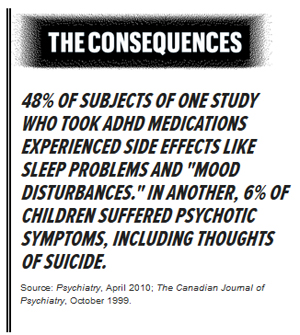

According to manufacturers of ADHD stimulants, they are associated with sudden death in children who have heart problems, whether those heart problems have been previously detected or not. They can bring on a bipolar condition in a child who didn’t exhibit any symptoms of such a disorder before taking stimulants. They are associated with “new or worse aggressive behavior or hostility.” They can cause “new psychotic symptoms (such as hearing voices and believing things that are not true) or new manic symptoms.” They commonly cause noticeable weight loss and trouble sleeping. In some children, some stimulants can cause the paranoid feeling that bugs are crawling on them. Facial tics. They can cause children’s eyes to glaze over, their spirits to dampen. One study reported fears of being harmed by other children and thoughts of suicide.

Imagine you have a six-year-old son. A little boy for whom you are responsible. A little boy you would take a bullet for, a little boy in whom you search for glimpses of yourself, and hope every day that he will turn out just like you, only better. A little boy who would do anything to make you happy. Now imagine that little boy—your little boy—alone in his bed in the night, eyes wide with fear, afraid to move, a frightening and unfamiliar voice echoing in his head, afraid to call for you. Imagine him shivering because he hasn’t eaten all day because he isn’t hungry. His head is pounding. He doesn’t know why any of this is happening.

Now imagine that he is suffering like this because of a mistake. Because a doctor examined him for twelve minutes, looked at a questionnaire on which you had checked some boxes, listened to your brief and vague report that he seemed to have trouble sitting still in kindergarten, made a diagnosis for a disorder the boy doesn’t have, and wrote a prescription for a powerful drug he doesn’t need.

Now imagine that he is suffering like this because of a mistake. Because a doctor examined him for twelve minutes, looked at a questionnaire on which you had checked some boxes, listened to your brief and vague report that he seemed to have trouble sitting still in kindergarten, made a diagnosis for a disorder the boy doesn’t have, and wrote a prescription for a powerful drug he doesn’t need.

If you have a son in America, there is an alarming probability that this has happened or will happen to you.

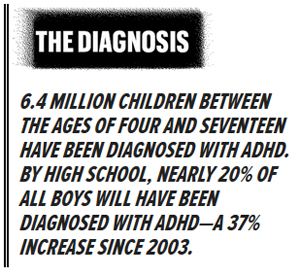

On this everyone agrees: The numbers are big. The number of children who have been diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder—overwhelmingly boys—in the United States has climbed at an astonishing rate over a relatively short period of time. The Centers for Disease Control first attempted to tally ADHD cases in 1997 and found that about 3 percent of American schoolchildren had received the diagnosis, a number that seemed roughly in line with past estimates. But after that year, the number of diagnosed cases began to increase by at least 3 percent every year. Then, between 2003 and 2007, cases increased at a rate of 5.5 percent each year. In 2013, the CDC released data revealing that 11 percent of American schoolchildren had been diagnosed with ADHD, which amounts to 6.4 million children between the ages of four and seventeen—a 16 percent increase since 2007 and a 42 percent increase since 2003. Boys are more than twice as likely to be diagnosed as girls—15.1 percent to 6.7 percent. By high school, even more boys are diagnosed—nearly one in five.

Almost 20 percent.

And overall, of the children in this country who are told they suffer from attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, two thirds are on prescription drugs.

And on this, too, everyone agrees: That among those millions of diagnoses, there are false ones. That there are high-energy kids—normal boys, most likely—who had the misfortune of seeing a doctor who had scant (if any) training in psychiatric disorders during his long-ago residency but had heard about all these new cases and determined that a hyper kid whose teacher said he has trouble sitting still in class must have ADHD. That among the 6.4 million are a significant percentage of boys who are swallowing pills every day for a disorder they don’t have.

On this, too, everyone with standing in this fight seems to agree.

But on the subject of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, that is where the agreement ends.

For example: Doctors, parents, and therapists give a lot of different explanations for the sharp rise. Increased awareness—that’s a big one. We know more now. Other possibilities put forth: Too many video games. Too much refined sugar. Pharmaceutical companies pushing ADHD drugs. Lack of gym classes at schools. All of these factors are cited. And people have a lot of different ideas about what to do for the children who receive these diagnoses. Many believe that medicine should be the first treatment, either combined with behavioral therapy or not. Others feel that drugs should be a last resort after making every other alleviative effort you can find or think of, from hypnosis to herbal treatments to neurofeedback.

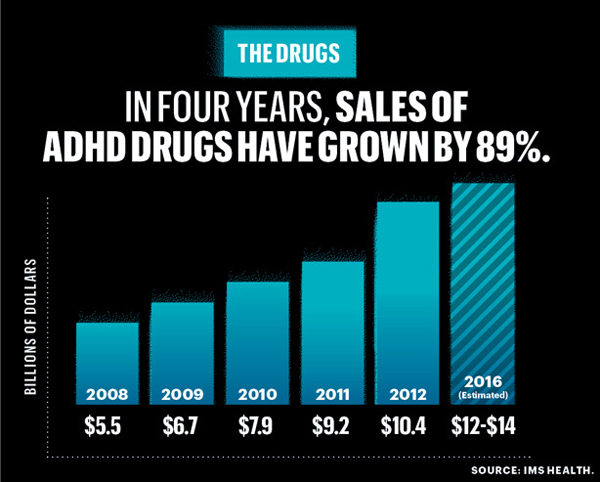

Given today’s prevailing pharmaceutical culture, clinicians who believe that drugs should never be used to treat ADHD in children are very much in the minority. Marketing is powerful, and blockbuster drugs like Ritalin are big business. Business booms, market share grows when scripts are written, and countercultural doctors and therapists who advocate caution and who believe that diagnoses are made too easily—doctors and therapists who preach alternatives to drugs—are finding themselves the butt of jokes.

Given today’s prevailing pharmaceutical culture, clinicians who believe that drugs should never be used to treat ADHD in children are very much in the minority. Marketing is powerful, and blockbuster drugs like Ritalin are big business. Business booms, market share grows when scripts are written, and countercultural doctors and therapists who advocate caution and who believe that diagnoses are made too easily—doctors and therapists who preach alternatives to drugs—are finding themselves the butt of jokes.

But more about them shortly.

The United States government first collected information on mental disorders in 1840, when the national census listed two generally accepted conditions: idiocy and insanity. A century later, psychiatrists knew more. They had options when making diagnoses, and by the 1940s difficult kids were classified as “hyperkinetic.” Other terms would follow, like minimal brain dysfunction. In 1955, there came a pill doctors could prescribe for these children to temper their hyperactivity and make them behave more like “normal” children. It was a stimulant, so called because it heightened the brain’s utilization of dopamine, which can improve attention and concentration. The active ingredient was a highly addictive compound called methylphenidate. The drug was called Ritalin.

By 1987, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) had settled on a more refined name for a disorder among children who exhibited the same set of symptoms, including trouble concentrating and impulsive behavior: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. ADHD. At the time, in American schools, it was still considered unusual for a child to take Ritalin. It was, frankly, considered weird.

Today, it has simply become a default method for dealing with a “difficult” child.

“We are pathologizing boyhood,” says Ned Hallo-well, a psychiatrist who has been diagnosed with ADHD himself and has cowritten two books about it, Driven to Distraction and Delivered from Distraction. “God bless the women’s movement—we needed it—but what’s happened is, particularly in schools where most of the teachers are women, there’s been a general girlification of elementary school, where any kind of disruptive behavior is sinful. What I call the ‘moral diagnosis’ gets made: You’re bad. Now go get a doctor and get on medication so you’ll be good. And that’s a real perversion of what ought to happen. Most boys are naturally more restless than most girls, and I would say that’s good. But schools want these little goody-goodies who sit still and do what they’re told—these robots—and that’s just not who boys are.”

Read the rest of the article here: http://www.esquire.com/features/drugging-of-the-american-boy-0414

SHARE YOUR STORY/COMMENT