Open Democracy – May 5, 2014

By Daniel George and Peter J. Whitehouse

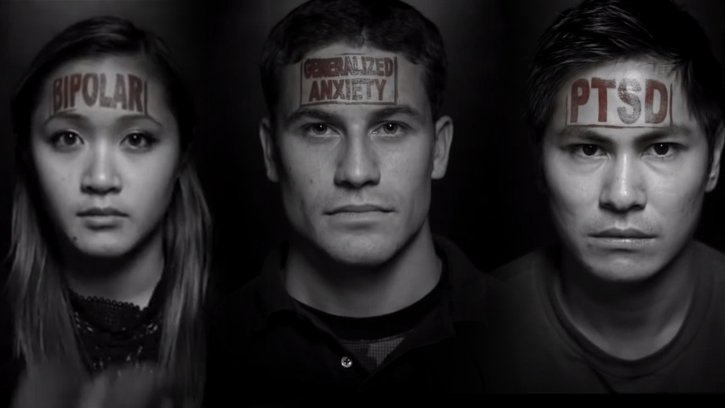

Being labeled ‘mentally ill’ can be an enormous burden: on individuals, their families, and their friends. It’s a label that can hang like an albatross around someone’s neck, instead of serving as a guide to the most appropriate support.

All such labels rest on a definition of what’s considered ‘normal,’ but normality is extremely contentious. Especially in privatized health systems like the USA, there’s a strong temptation to skew this definition towards the interests of business and the medical establishment.

In that way, feelings and behaviors classified as mental illnesses can open up new profit centers for drugs and other interventions in the nexus between capitalism and healthcare.

The evolution of the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual” – the ‘bible’ of American psychiatry – is a classic illustration of this process at work.

Concepts of suffering and anguish have always varied across historical and cultural contexts, and they manifest in the body in many different ways. For example, the autism spectrum has variously positioned people as being intertwined with the spirit world and deserving of elevated status, or disabled to the point of requiring highly-specialized treatment for remediation.

Being ‘out of touch with reality’ can be a simple assertion made by one faction against another – take climate change advocacy and denial, for example. Or it can be re-labeled as a ‘psychosis.’ When a dream becomes a hallucination or suspicion rises to the levels of clinical paranoia, then a psychiatrist might consider treatment with powerful medication. But recent revelations about the highly-intrusive monitoring of personal communications by America’s National Security Agency suggest that the boundaries between paranoia and the appropriate level of suspiciousness are already indistinct.

Psychiatric concepts, methods of research and even data are not ‘givens.’ They are all embedded in social systems, and shaped by cultural, political and economic forces.

These uncertainties present many challenges to health care and society. Are mental illnesses medical conditions just like disorders of the body, which therefore deserve equal attention, support and payment by health care systems?

Or are they fundamentally different, related to existential anxieties perhaps, or to the particular pressures associated with living in complex, interdependent communities which have powerful social and cultural scripts about normality? Do such conditions exist on a continuum, or do they represent diagnostic categories that are discrete?

Although medicine is often looked to to provide objective answers to these questions, modern psychiatry has itself been labeled the “Mad Science” in a recent book. Why? Because psychiatrists have consistently expanded the boundaries of disease, using scientific claims that are only weakly supported by the evidence.

Consider, for example, a number of controversial labels that have been invented by psychiatrists: “Sluggish Cognitive Tempo,” said to be characterized by lethargy, daydreaming and slow mental processing; “Mild Cognitive Impairment” – a supposed precursor to Alzheimer’s disease; and “Restless Leg Syndrome” – the aberrant urge to move one’s legs. We’ll return to these conditions a little later.

Labels like these are promoted by scientists and their allies in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries. They evoke much anxiety about the ‘normal’ physical and mental functioning demanded by a capitalist economy.

But are thinking and moving faster always a healthy and effective response to the challenges of modern life? Is it the role of psychiatrists to define what is meant by happiness and sadness?

Such questions have profound implications for individuals and communities.Science and commerce are running amok, and nowhere is this more evident than in psychiatry.

Since 1952, North American psychiatrists have tried to categorize mental illness into discrete, scientifically-grounded and therapeutically-relevant categories as part of an ongoing document called the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual” or “DSM.” In the decades that followed its release, this manual underwent significant revision, rising from 106 categories of mental illness in its first iteration to over 300 in the fifth and most recent version that was released in 2013: the “DSM 5.”

Despite its aura of objectivity, the DSM is really an historical document that reveals the assumptions, fallacies and foibles of each moment in time.

Homosexuality, for example, was codified as a “disease” until 1973. The latest version has been severely criticized by those involved in putting previous editions together, such as Alan Frances, whose recent book title says it all: “Saving Normal: An Insider’s Revolt Against Out-of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life.” Frances is not alone. Thomas Insel, the Director of the National Institute of Mental Health, denies that DSM 5 is based on adequate science and has stopped funding any research that uses it.

Why is the process of compiling the DSM so controversial? One reason is that every time the manual is revised, more people are labeled as ‘mentally ill,’ so much so that establishing criteria for being ‘normal’ has become just as important. As the challenges mount up from rising injustice and inequality, population growth and climate change, it may be difficult for any of us to maintain our mental health. But it will be even more difficult to avoid the label of mental illness if psychiatrists are encouraged to use more and more sophisticated diagnostic tests like “neuroimaging” in order to detect the smallest deviations from the norms they manufacture. All labels can be liberating or enslaving.

At the center of the search to find new labels and modify existing ones are the hubris of doctors and the profit-making tendencies of the pharmaceutical industry, which play an integral role in the process of defining new categories of disease. Take autism. In DSM 5, the label “Asperger’s” was replaced by the concept of a “spectrum of autism.” That’s important because people diagnosed with Asperger’s often have high intellectual abilities. Some are particularly adept at using information technology and thinking about complex systems, but most are challenged by social interactions. However, that doesn’t make them mentally ill under the new label of “autistic.”

Another controversial change was to eliminate the six-month waiting period that was put in place to allow grief to dissipate after a life trauma, before it is classified as “clinical depression.” Now you can have your “serotonin reuptake blocker” prescribed the day after a loved one dies. By dissolving the boundary between normal sadness and mental illness, DSM 5 allows depression to be diagnosed without consideration for the context of grief.

Or take the case of dementia, which has been semantically “cured” in DSM 5 by replacing this label with a new category called “Major Neurocognitive Disorder.” This linguistic sleight-of-hand was designed to diminish the stigma connoted by the word “dementia” in English and many other languages. Yet one wonders whether the American Psychiatric Association (APA) has the power to do this simply by changing words.

As we mentioned earlier, DSM 5 has also produced other categories like “Mild Neurocognitive Disorder.” This label recognizes the obvious but much ballyhooed observation that people can have degrees of cognitive impairment that don’t affect daily living in any significant way, at least in the early stages. But why “mild” and not “minor?” The answer is that the APA didn’t feel that anything described as “minor” would be reimbursable by health insurance companies – a vital ingredient of the American health system in which repayments for drugs and therapies are tied to diagnostic labels.

This example takes us to the heart of the matter. The APA makes a considerable amount of money by selling the DSM. “Big Pharma” makes much more money by extending the diagnostic categories contained in the manual or by inventing new categories altogether, in order to create and widen their markets. The best strategy of all is to “repurpose” a drug for use beyond its original indications. For example, drugs for Parkinson’s disease have been reassigned to “Restless Leg Syndrome.” Repurposing drugs is not unethical in itself, but it has led to considerable unethical behavior when doctors and drug companies combine to push treatment in this direction. Pharmaceutical companies are not permitted to market such extensions of use. Yet they make billions of dollars from doing just this. Large fines imposed for such behavior by government are considered a price well worth paying – “marketing expenses,” if you will.

One of the strongest critics of “big pharma” and their scientist-doctor allies is Peter Gotzsche, a clinician, evidence-based medicine expert and former pharmaceutical company employee. His recent book “Deadly Medicines and Organized Crime: How Big Pharma Has Corrupted Healthcare” is one of a growing number of works which problematize and publicize the dangerous and subversive relationships that exist between doctors, drug companies, politicians and health insurers.

The corporatization of healthcare, in which expanded categories of mental illness play a growing role, has produced a system that is both unethical and dysfunctional – perhaps even ‘culturally demented’ in the ways in which it medicalizes naturally-occurring disorders of the brain.

As the story of the DSM shows, this ‘cultural dementia’ has moved from being a mild to a major neurocognitive disorder of its own. It’s time to bring back some sanity to the world of mental health.

—

Peter J. Whitehouse, MD, PhD is Professor of Neurology at Case Western Reserve University and Professor of Medicine at the University of Toronto. He is co-founder of The Intergenerational School and a strategic advisor in innovation. His scholarly interests include neuropsychiatry, cognitive neuroscience, environmental ethics, narrative medicine and multimedia.

Daniel R. George is an assistant professor in the Department of Humanities at Penn State College of Medicine. He holds a doctorate in medical anthropology from Oxford University.

SHARE YOUR STORY/COMMENT